“Iff explained that these were the Streams of Story, that each coloured strand represented and contained a single tale. Different parts of the Ocean contained different sorts of stories, and as all the stories that had ever been told and many that were still in the process of being invented could be found here, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was in fact the biggest library in the universe. And because the stories were held here in fluid form, they retained the ability to change, to become new versions of themselves, to join up with other stories and so become yet other stories; so that unlike a library of books, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was much more than a storeroom of yarns. It was not dead, but alive.” Salman Rushdie, Haroun and the Sea of Stories

“Iff explained that these were the Streams of Story, that each coloured strand represented and contained a single tale. Different parts of the Ocean contained different sorts of stories, and as all the stories that had ever been told and many that were still in the process of being invented could be found here, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was in fact the biggest library in the universe. And because the stories were held here in fluid form, they retained the ability to change, to become new versions of themselves, to join up with other stories and so become yet other stories; so that unlike a library of books, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was much more than a storeroom of yarns. It was not dead, but alive.” Salman Rushdie, Haroun and the Sea of Stories

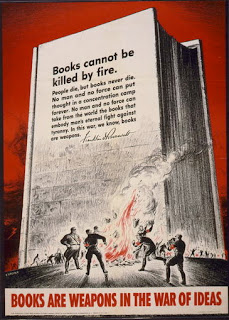

I confess to being a huge Rushdie fan, not so much because of his work (although Midnight’s Children is arguably one of the greatest novels of world literature), but because I have heard him speak – about stories, and about the experience of being in fear for his life because of storytelling. For those of you too young to recall, Salman Rushdie’s novel, The Satanic Verses, brought down the wrath of the Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran with a fatwa, a sentence of death, in 1989. In short, the Ayatollah said that his followers had an obligation to execute Rushdie. There was a huge international outcry that continued for years; nevertheless, Rushdie was forced into hiding for several years, truly in mortal danger while violence and book burnings erupted around the world. It was appalling.

|

| WWII poster protesting Nazi book burnings |

His first book after this experience was Haroun and the Sea of Stories, a fantastical riff on the 1,001 Arabian Nights which he wrote, he said, partly to explain to his son what had happened to him. The control of stories and storytelling is one of the first things on every dictator’s to-do list; can there be any better evidence about the power that stories have? As the tyrant in Haroun complains, inside every story is a world that he can’t control.

Authoritarian regimes fear the independence of thought and action that stories encourage. In my role as the Lovely K.’s personal bard, I must always be on the lookout for my own motives in choosing or not choosing a story for her. If I pass over a story because I’m afraid it will “give her ideas,” then I probably should go back and tell that story without delay! As a parent I am a one-person authoritarian regime, but if I must be a dictator then I can at least strive to be an enlightened and benevolent one. After all, independence of thought and action is what I’m trying to teach my daughter. Isn’t that what we mean by courage?

“Iff explained that these were the Streams of Story, that each coloured strand represented and contained a single tale. Different parts of the Ocean contained different sorts of stories, and as all the stories that had ever been told and many that were still in the process of being invented could be found here, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was in fact the biggest library in the universe. And because the stories were held here in fluid form, they retained the ability to change, to become new versions of themselves, to join up with other stories and so become yet other stories; so that unlike a library of books, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was much more than a storeroom of yarns. It was not dead, but alive.” Salman Rushdie, Haroun and the Sea of Stories