Monthly Archives: October 2011

Courage Quote of the Day

About Stories

“We construct a narrative for ourselves, and that’s the thread that we follow from one day to the next. People who disintegrate as personalities are the ones who lose that thread.”

~ Paul Auster

Don’t Be Scared!

Other friends lived in similarly old, minimally electrified, cavernous houses on large properties with tumble-down barns, sheds, guest houses, gazebos, stables, etc. This was the 60s and 70s, in rural New York, and the gentrification push from New York City hadn’t yet begun. One of my friends actually lived on the grounds of a sprawling old mental hospital, and we wandered freely, poking our noses into rooms, or trying to wipe the grime off the windows of locked buildings so we could spy. We played in settings that have become horror movie standards, but back then it was just normal: usually fun, occasionally mysterious, with a once-in-a-while dip into real fright. But still normal. It was the brand-new homes with wall-to-wall carpeting, bright overhead lights, and shiny matching appliances that were truly foreign to me. Only one of my friends lived in such an outlandish house as that.

I don’t know how many kids today get to roam around by themselves in such liminal spaces. As you may recall from my post about bedtime stories, liminal refers to thresholds. These places are neither here nor there, inside nor outside, inhabited nor empty. They are all between. They are openings, waiting in suspended time. It is here that the hero can experience the call to adventure, the invitation to step into the unknown and begin the quest. Yes, there is fear in the unknown, and fear in shadowy spaces. But I think that I, for one, spent much of this time unconsciously testing myself, measuring my courage against the courage I discovered in stories. If I had discovered a wardrobe that led into another world, I would have been ready.

Courage Quote of the Day

Courage Book Review – Baba Yaga and Vasilisa the Brave

Raising a Good Citizen of the World

~ Eric Greitens, Author of The Heart and The Fist: The Education of a Humanitarian, The Making of a Navy Seal (2011)

So, what’s a parent to do to help raise a good citizen in this world?

So, what’s a parent to do to help raise a good citizen in this world?

Let’s face it our kids need to be equipped to be able handle increasingly complex moral issues involving a multitude of cultures participating together in a global economy (stacked precariously on questionable foundations), with exponential population growth, and environmental concerns that don’t leave any corner of our globe unaffected. The ripple effect of our daily decisions from how treat our neighbor, to whether to vote or not, to where we spend our money, to how we deal with our garbage now send ripples farther and wider than ever before in history. Learning to solve our planet’s problems in sustainable, cooperative ways is more important than ever!

-

Nurture a strong, secure, and loving bond with your child from infancy through adolescence. Through this bond, you can become a powerful mentor for your child—especially during tough times.

-

Show empathy and compassion for others. Share out loud your curiosity about how others feel, think, believe, and live. Make it okay to discuss differences and notice all the similarities the human family shares.

-

Offer lots of opportunities through family time and socialization opportunities for your child to develop care and concern for others, their community, and the environment.

-

Model the values you wish your child to embrace: honesty, kindness, etc.

-

Define the values that matter to you as a family, notice them in your everyday life, discuss why they are important to you? Pick a value a week, like those Lion’s Whiskers associates most with moral courage:· Loyalty· Trust· Honesty· Integrity· Accountability· Responsibility· Fairness· Impartiality· Justice.

-

Show self-discipline in creating the kind of life you wish them to emulate.

-

Teach goal-setting and decision-making skills.

-

Discuss and weigh the pros and cons associated with simple and complex moral dilemmas involving not only “right vs. wrong,” but also even more complicated “right vs. right” or “wrong vs. wrong” scenarios.

-

Show respect for yourself and others, especially your children.

-

Put the Six Types of Courage into action—let your child witness you walking your talk, taking personal responsibility, and having the courage to stand up for what you believe in.

-

Embrace a multicultural perspective for what is good and right in this world—you don’t have to eat, marry, or pray like others, but you can still model respect and tolerance for differences. You can venture to be curious about, seek to understand, and even embrace different cultural beliefs as appropriate.

-

Model what a good citizen is for your child, and work together to make your family, community, and the world-at-large a better place to live. Seek out lots of opportunities to do good and be charitable in the world together.

-

Pick a cause you believe in to contribute your time, money, signatures, and care to as a family.

-

Praise your child when they act in ways that are moral, good, and in sync with your family values.

-

Provide a community of like-minded friends, family members, teachers, religious and/or civic leaders for your child to learn from.

-

Tell stories from your own life or those of moral courage heroes you respect.

- Read traditional moral tales (this is a link to Jennifer’s bookshelf) and discuss the life lessons they understand imbedded within the story. Jennifer regularly provides tales to choose from in her previous posts, too! Just click on this link to find a treasure trove of moral courage stories to share. Help them put into their own words the moral of the story, see if they can offer an example from their own life when they’ve had to “never give up,” “do the right thing,” “tell the truth,” or “be loyal to a friend”. Highlight future opportunities for them to put into practice the particular value you wish them to emulate. Narvaez, Gleason, Mitchell, and Bentley (1999) caution parents and teachers that simply reading moral stories to children does not guarantee their understanding of the core moral message. In the imagination of a five year-old, a story like The Little Engine That Could (1930), the “Little Engine” could be faced with the nonmoral theme (one highly related to courage) of simply never giving up. A nine year-old reader, on the other hand, may relate to the underlying moral lesson pertaining to importance of perseverance in order to help others. As children mature, and their prefrontal cortex continues to develop into young adulthood, they are capable of increasingly complex interpretations and better able to identify complex moral dilemmas and a story’s underlying moral message.

For more guidance about how to help your child become a responsible citizen, Navaraez (2005) helped develop this downloadable book, thanks to funding from the U.S. Department of Education and the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001.

How are you raising your child to be a good citizen? We’d love to hear your ideas, too!

Courage Quote of the Day

The Sea of Stories

“Iff explained that these were the Streams of Story, that each coloured strand represented and contained a single tale. Different parts of the Ocean contained different sorts of stories, and as all the stories that had ever been told and many that were still in the process of being invented could be found here, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was in fact the biggest library in the universe. And because the stories were held here in fluid form, they retained the ability to change, to become new versions of themselves, to join up with other stories and so become yet other stories; so that unlike a library of books, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was much more than a storeroom of yarns. It was not dead, but alive.” Salman Rushdie, Haroun and the Sea of Stories

|

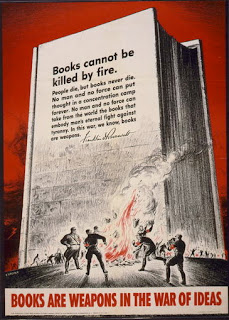

| WWII poster protesting Nazi book burnings |

His first book after this experience was Haroun and the Sea of Stories, a fantastical riff on the 1,001 Arabian Nights which he wrote, he said, partly to explain to his son what had happened to him. The control of stories and storytelling is one of the first things on every dictator’s to-do list; can there be any better evidence about the power that stories have? As the tyrant in Haroun complains, inside every story is a world that he can’t control.

Courage Book Review – Why Courage Matters, by John McCain

In Why Courage Matters: The Way to a Braver Life we have a small, accessible book for adult readers (or teen readers, of course) by Senator John McCain with Mark Salter. McCain has been rightly honored for the courage he demonstrated as a POW, and regardless of your political opinions of his public service in the U.S. Congress, his is a voice of experience on this issue. He brings to this exploration of courage a not suprising inclination to praise military heroism, but there’s much more than that. One thing that I like about this book is that he does discuss courage as something for parents to heed, and to strive to develop in their children. He offers many examples from history of tremendous courage, from soldiers on the front lines to civil rights activists using nonviolent disobedience to further their cause. I have three takeaways from the book: